|

|

Post by marklemon on Mar 12, 2010 0:14:08 GMT -5

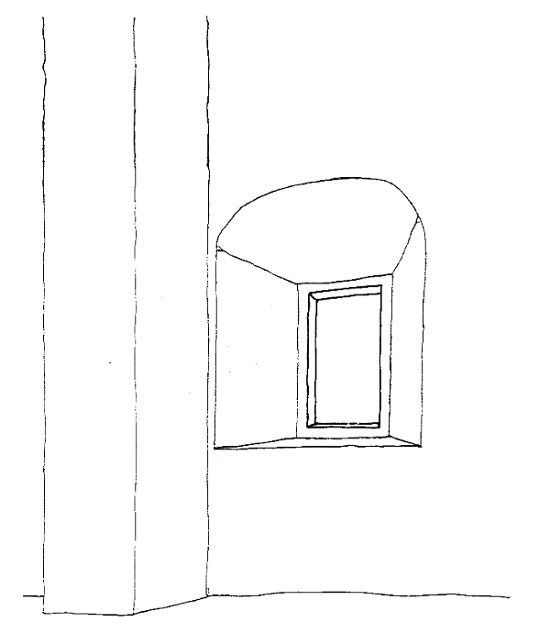

While perusing Rexford Newcomb's "Spanish Colonial Architecture in the United States," I happened upon something very interesting. On page 47, there is a plan view of Mission San Xavier Del Bac near Tucson, AZ. The plan is quite similar to the church at Mission San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo) in overall configuration. Located in virtually the exact same spot in the nave as the recently found aperture in the Alamo, is a splayed window. Clearly, these windows were deemed helpful in admitting the maximum amount of light into an otherwise dark space.

|

|

|

|

Post by TRK on Jun 3, 2010 16:42:39 GMT -5

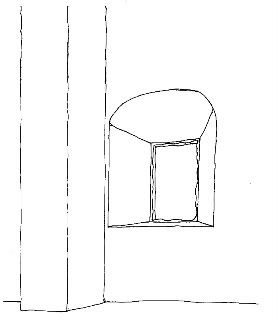

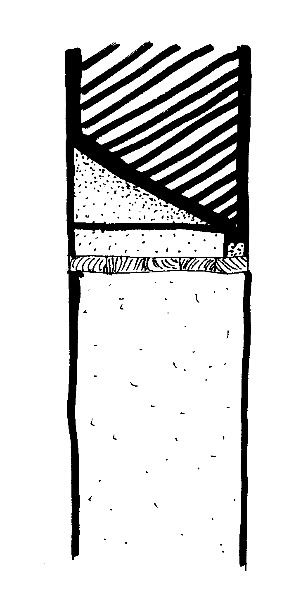

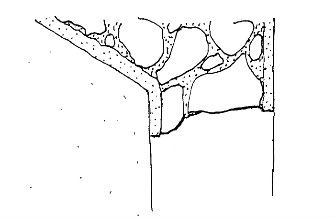

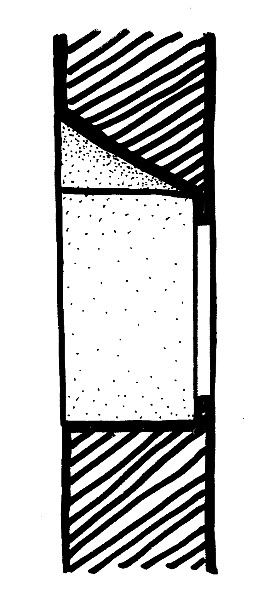

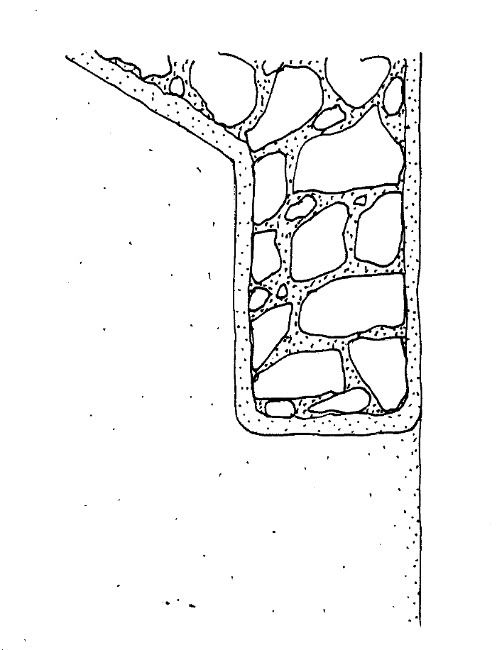

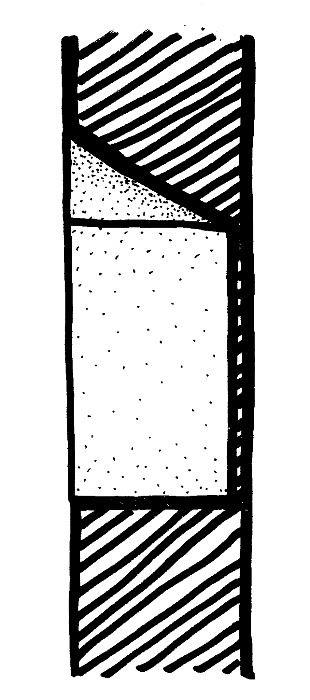

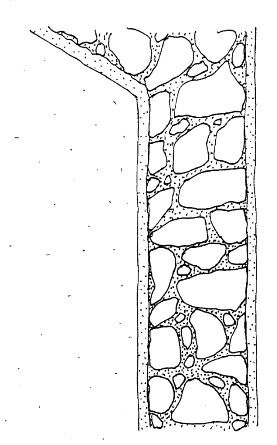

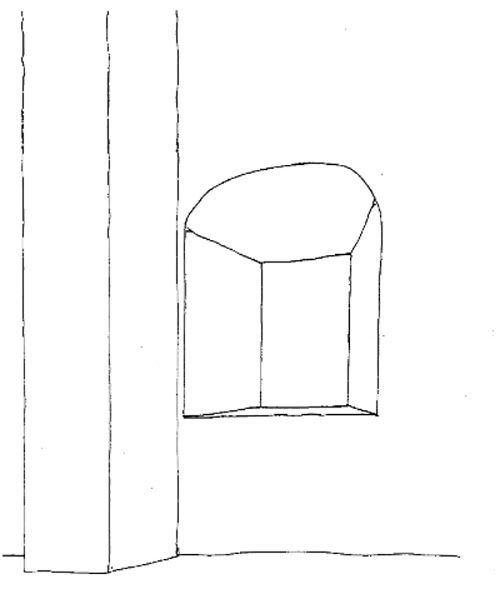

[Note: Forum member Jake Ivey submitted the following document with photos, which I am posting at his request:] The recently found opening in the south wall of the MBC looks like this after it was cleaned out and stabilized. This is a somewhat out-of-focus or low-resolution photograph, probably from a cell-phone. Below the wooden lintel, the preservationists have left the stone fill in place.  Not quite visible on the surface of the curved upper face of the opening is the date 1848 scratched into the plaster. The opening looked something like this just before the U S Army cut out the stonework at the bottom of the opening so that it could be made into a doorway. Around the inner edges of the opening is an irregular broken edge, visible along the top of the opening in the photograph, where the back section of the opening, about 5 inches thick, had been broken out as part of the process of converting this opening to a doorway.  In cross-section, the present doorway and the new arched opening look like this:  The broken edge along the top looks something like this in closeup:  It is mostly made up of stones and broken cobbles mortared together, with a final coat of mortar to give it its final shape, and a thin layer of whitewash over that. The broken-out plaster and stone lip is about 5 inches thick, while the wall itself is about four feet thick. But how far out from the inner edge of the opening did the lip extend? Perhaps it extended five or ten inches – if so, the opening looked like this:  And the edge itself looked like this:  This would make the opening look like this:  But there is no surviving portion of such a finished surface anywhere on the parts of the broken edge that we can see. In other words, there is no evidence that lets us say that this is the way the opening looked. It is equally possible that the broken-out area extended across the entire opening, like this:  . . . so that the close-up looked like this:  . . . and the opening looked like this, with a walled-off back:  If this was the case, the opening would have been a niche in the south wall of the MBC, rather than a window through into the nave. From the nave side, the area would have been a solid wall, although only about 5 inches thick where the niche was. The physical evidence as we have it now does not let us say it was one or the other – we have to decide that using other considerations. Our only description of this opening is in the 1793 inventory of the mission, the “Ymbentario de las existencias q e hay hoy dia 23. de Abril de 1793. en la Mis[ion] de San Antonio Valero,” a copy of which is in roll 4, frames 5808-5816, of the Old Spanish Missions Historical Research Library microfilm collection at Our Lady of the Lake University, San Antonio, Texas.

[5808] "La Sacristia: De d[ic]ha Yglesia es de doce varas de largo, con 5. de alto, y 5½ de ancho esta buena, y sirviendo de Yglecia. Sus Vovedas son aristas estan [5809] buenas con sus enjarres, y blanqueados. Tiene dos puertas de Piedra labrada, la una qe entra á otra p[ie]za desde el cuerpo de aquella, qe sirve de sacristia, y tiene 8a varas de largo, y 7a de ancho con sinco, y media de alto, techada de madera de zedro, sustentada de un arco rebajado, que dibide por medio d[ic]ha p[ie]za, el qual está mui lastimado, sostenido por puntales de madera; tiene puertas al oriente, y Norte, con dos ventanas, qe miran a el sur, y Poniente, y las puertas tienen sus chapas, con aldabas, y con enrrejado de fierro la de el oriente..."

"The Sacristy: of the said church is 12 varas [32.9 feet] long, 5 [13.7 feet] high, and 5½ [15.1 feet] wide, and serves as the church. Its vaults are groined; they are good with their plastering and whitewash. It has two doorways of carved stone, one that enters another room from the interior of the one that serves as the sacristy; it has 8a varas [22.8 feet] of length, and 7a [20.1 feet] of width, with 5½ [15.1 feet] of height, a roof of cedar, supported by a segmental arch that divides the said room in half; the which [roof] is very leaky, [and is] supported by poles of wood; it [the acting sacristy] has doorways to the east and north, with two windows that look to the south and west [my emphasis], and the doors have their locks, with latches, and that [door] to the east has a grill of iron..."

In the MBC, the temporary sacristy, probably against its west wall, was a large cabinet 5 varas (13.7 feet) long, lined with leather, and with eight large drawers and two cupboards, one on each end, and a front door of carved wood, all of which contained the vestments and silver for the temporary church.

The second doorway opening from the MBC to the north went into a smaller room at the east end of the south row of convento rooms. Traces of the northern doorway can be seen on the north wall of the MBC. Today there is a doorway from the MBC into the nave through the south wall, and up until recently there was no trace of a window. The present doorway opening was chopped through the wall sometime after 1848, when the date was scratched on it, and it is not shown on the Army plans of the church made in that year.

The only other inventory description of the MBC we have, the one made in 1772 (Inventory of the Mission San Antonio de Valero: 1772, translated and edited by Benedict Leutenegger, Special Report 23, Office of the State Archeologist, Texas Historical Commission, Austin, 1977), pp. 8-9, describes the large cabinet in the room, but does not mention a window through the south wall. Like the 1793 inventory, the 1772 inventory does not mention a window through the north wall of the nave of the church.

I have always assumed that the present doorway obscured or obliterated the traces of the “window” in the south wall mentioned in the 1793 inventory. Because the 1793 inventory does not mention a window in its description of the interior of the incomplete church, I also have assumed that the word “window” was incorrect, and that what was being described was a niche that did not extend all the way through the wall. Now that an opening has been found, but not in the form I would have expected, I have had to look again at these assumptions. My conclusion is that there are still problems with accepting the 1793 description of the opening in the south wall of the MBC as a window.

If you stand in the nave of the Alamo church today, back a ways from the present MBC doorway, and imagine the MBC opening as a window in the wall of the nave, you will be struck by the realization that it is very small and very low – it looks far too small and low to be a window in any meaningful way. And because a mission church is full of valuable utensils on the altar, the church was never left open, because someone without the proper piety could walk off with the candlesticks or other silver objects. Such a low window would have some means of closing it, such as shutters or an iron grill, like the one on the door into the sacristy mentioned in the 1793 inventory above – but there is no trace of shutters or the sockets for grill-work on the parts of the opening we can see.

The opening is of the same appearance, the same style, as the other openings, the doorways and windows, that survive in the MBC and the sacristy. They are all cleanly rounded and covered with a smooth coat of finishing plaster. The available evidence indicates they were all built by the same master mason, Joseph Palafox, in the 1760s.

When the church and the adjacent section of the convento were begun by Antonio Tello in the early 1740s, it appears that he intended the area of the MBC to be an open courtyard east of the north bell-tower of the church, and the walls of the entire church and new parts of the convento were left with walls standing perhaps 4½ feet high on his departure in 1744.

About 1755, with the completion of their work at both the parish church of Candelaria in downtown San Antonio and the church at the mission of Concepción, the master mason Hieronymo Ybarra and the master sculptor Felipe de Santiago were hired by the Franciscans to rebuild the ruined church of Valero. He seems focused his efforts on the construction of the church, and did little work on the sacristy. When Ybarra left San Antonio about 1760, the sacristy at Valero was apparently ready to receive its vaulted ceiling, and the space to its west was still the open courtyard planned by Antonio Tello.

The Franciscans hired Joseph Palafox to take Ybarra’s place in the effort to finish Valero. He arrived at Valero in July, 1761. Over the next three years, Palafox probably built the vaulted ceilings of the ground floor rooms of the bell towers, and began the sacristy vaults and the vault that would support the choir loft. About 1763, Palafox seems to have finished the vaulted roof of the sacristy, and church services were moved to this room from the temporary church in the granary, today the north half of what is called the Long Barracks.

It was apparently Joseph Palafox who enclosed the patio next to the sacristy as well, roofing it so that it could serve as the temporary sacristy. It is likely that as part of the work on these two rooms, Palafox designed and built all the doorways and windows of both the MBC and the sacristy. This would explain why all the stone-work was so similar: it was all designed and built by a single master mason over a period of about three years in the 1760s.

However, this sequence of events would indicate that the opening could not be a window, because the MBC as completed was an enclosed, roofed room – the opening, if it indeed opened into the nave of the church, was not a window to the outside, and did not let in light from the northern sky, but always opened into the MBC. This suggests that if it was a window-like opening, it served some other purpose, such as perhaps being covered with a wooden grill and being used as a confessional window.

These considerations suggest that the statement in the 1793 inventory that the opening was a window was a mistake made by the persons who prepared the description of the church, and that it was in fact a niche that did not go entirely through the wall into the nave, or a confessional window covered with a grill.

-Jake Ivey

|

|

|

|

Post by Jim Boylston on Jun 3, 2010 17:04:45 GMT -5

Great info. Many thanks, Jake!

|

|

|

|

Post by Paul Sylvain on Jun 3, 2010 19:50:39 GMT -5

Fantastic stuff. I'll be back in San Antonio and will, of course, visit the Alamo again. I'll be curious to see how this work is progressing, if at all, since I was there for the HHD in May.

Paul

|

|

|

|

Post by marklemon on Jun 3, 2010 21:12:52 GMT -5

Thorough analysis Jake. And takes a lot of thinking on.....

What bothers me though, is that the inventory clearly states it is a window.... To believe it otherwise, we have to dispute what an eye witness clearly states is there. The fact that it was not mentioned as being in the nave may be an oversight, or it may have been shuttered and thus not noticed, or not thought to have been significant enough to make specific mention of with all the other interior features extant and needing description in the church proper.

We've seen before that the "absence of evidence" is not necessarily "evidence of absence," and this maxim may apply in the nave's description. There may be a hundred reasons why a thing is not mentioned (not noticed, not seen, forgotten about, etc) but there are only a very, very few reasons why something is seen, and mentioned, but is not there....In other words, to explain or otherwise make the very specific mention of a window in the south wall of the temporary sacristy "go away," we must chalk it up to a lie or a mistake. I'm not so sure I'm ready to do that.

I have seen a few other examples in Franciscan architecture of niches with flat interior surfaces, however when they are so configured, they seem to consistently have perpendicular, non-splayed sides. But when a niche does have curved, or splayed sides, it has a rounded planform (curved back surface). So, if this feature is in fact a niche, it does not have a precedent in Franciscan or Spanish Colonial architecture that I am aware of (which isn't necessarily saying anything!).

So if it is not what it clearly appears to be (ie: a window) we have to accept that it is what it does NOT appear to be,(ie: a niche).

The presence of a splayed top and sides usually indicates the admittance of light, and is very consistent with a window. In short,

I've seen niches with perpendicular sides, and a flat back, and curved sides which curve all the way through the niche's contour. But I have not seen a niche with a combination of splayed sides and flat back. There may be examples, I just don't know of any....

The apparent lowness you mention of the window (if that's what it is) goes away when we add another foot and a half of depth by removing the modern build-up of subfloor and flagstones. Not too high of course for someone with a ladder, but very much too high for someone without one. And remember, this window would be for all intents and purposes, accessed from the relative security of the convento cloister, and could not be reached from the exterior of the mission.

The church at San Xavier del Bac, near Tucson, AZ, has such a window in virtually the same spot in the nave as this one. Also, there is another church (San Blas?) in Mexico with a similar one as well. There may be others, but those two come to mind....So, on the whole, I'm still strongly leaning towards a window, until clear, and very persuasive contradictory evidence comes along.

Mark

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen Wiener on Jun 3, 2010 21:52:01 GMT -5

Very interesting, Jake; thanks for posting that!

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Jun 4, 2010 11:42:52 GMT -5

Mark is right. The documentary evidence -- that is, the statement that there's a window on the south wall of the MBC in 1793, is a clear and annoying obstacle to any arguments for a different interpretation of the thing. But still, the physical history strongly suggests that when this "window" (that's not sarcasm, I just don't know what to call it that's neutral) was built, it opened into a room, not to the sky. So it wasn't made as a source of light. So what was it made for, if it was an opening?

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Jun 4, 2010 18:05:27 GMT -5

This is a post-script to my previous message -- I'll be out of town on a trip to England and Scotland for the next three weeks (pubs and Roman ruins -- zowie!) and may have trouble connecting with the Forum occasionally. WiFi is a little thin in parts of Devonshire. But I'll try to be in touch at least every few days.

Jake

|

|

|

|

Post by marklemon on Jun 4, 2010 18:08:42 GMT -5

Jake,

If Ybarra ( pre-1760) never intended to have the patio covered, which seems to be the case, then the window opening into it from the nave would make perfect sense. Light reflecting into the nave from the patio area as the day wore on, would be a welcome feature in the otherwise dark western part of the nave.

It was only post-1760, when Joseph Palofox took over, and roofed over the MBC, that the window then became an anomaly. Or am I missing something...?

Mark

|

|

|

|

Post by Jim Boylston on Jun 4, 2010 19:11:42 GMT -5

Jake, color me envious! Have a great trip.

Jim

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen Wiener on Jun 4, 2010 20:43:46 GMT -5

Hey, Jake; lift a pint for me, will you? I miss that territory.

Allen

|

|

|

|

Post by marklemon on Jun 4, 2010 21:08:34 GMT -5

Jake, try a big steaming plate of haggis when you're in Scotland......an underrated delicacy!

Mark

|

|

|

|

Post by Kevin Young on Jun 7, 2010 12:50:00 GMT -5

Jake-great discussion. Thanks for trying to make sense of it.

Hope you have a great trip.

|

|

|

|

Post by Mike Harris on Jun 7, 2010 18:14:57 GMT -5

The church at San Xavier del Bac, near Tucson, AZ, has such a window in virtually the same spot in the nave as this one. Also, there is another church (San Blas?) in Mexico with a similar one as well. There may be others, but those two come to mind....So, on the whole, I'm still strongly leaning towards a window, until clear, and very persuasive contradictory evidence comes along. Mark The window at San Blas (or at least 5 windows as it appears here) appear to be specifically for a light source of the nave. I say this only because I am fairly certain there is nothing on the outside of the wall to the right of the photo. Therefore a window, or windows, in this location makes perfect sense. Unfortunately, I'm not so sure what is on the other side of the wall to the left.  Also, it's almost impossible to tell from this photo, but the lower ledge of the window stands roughly 5-6 feet from the floor. Based on that, I'm not exactly sure how large that makes the San Blas window, but whatever it's measurements, it would seem to dwarf the window, niche,  at the Alamo. This means nothing to the discussion regarding the niche/window at Valero, I just thought the comparison with San Blas was interesting. Mike |

|

|

|

Post by marklemon on Jun 7, 2010 18:35:21 GMT -5

Mike,

If I read Jake's dates correctly, the nave window would have been built in the Alamo at a time during which the space on the other side of it (MBC) was an open patio, thus making sense of it's placement.

Mark

|

|