|

|

Post by bmoses on Dec 30, 2007 17:00:11 GMT -5

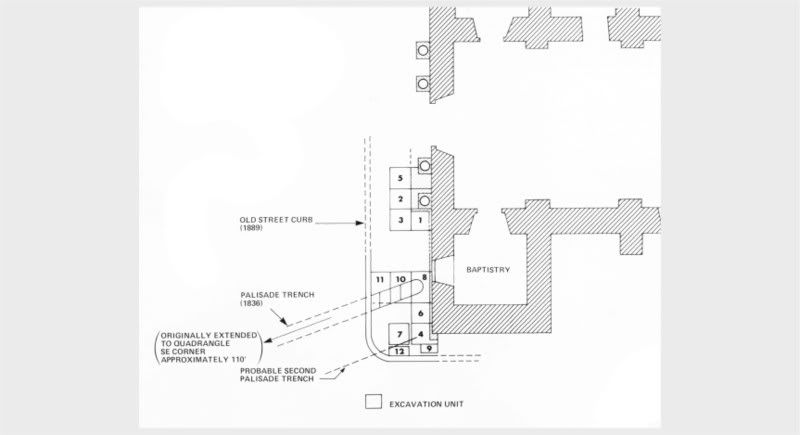

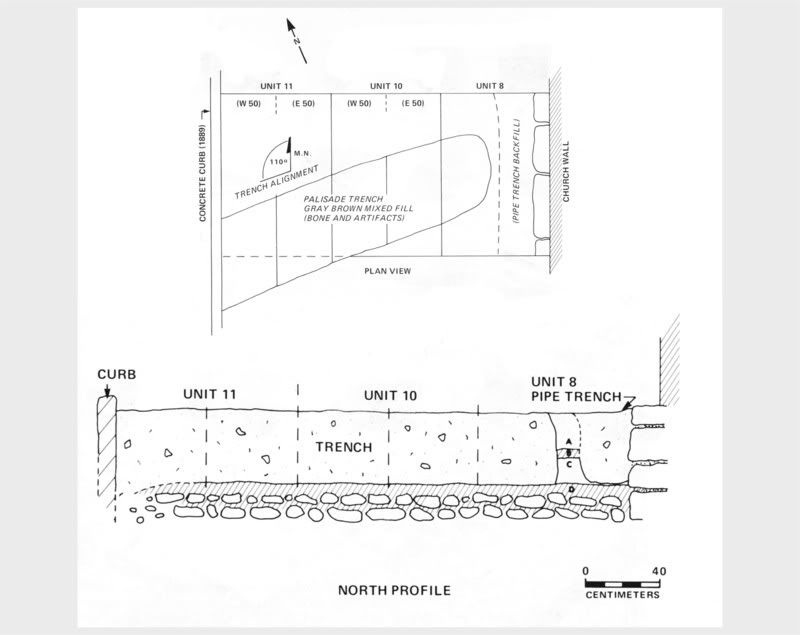

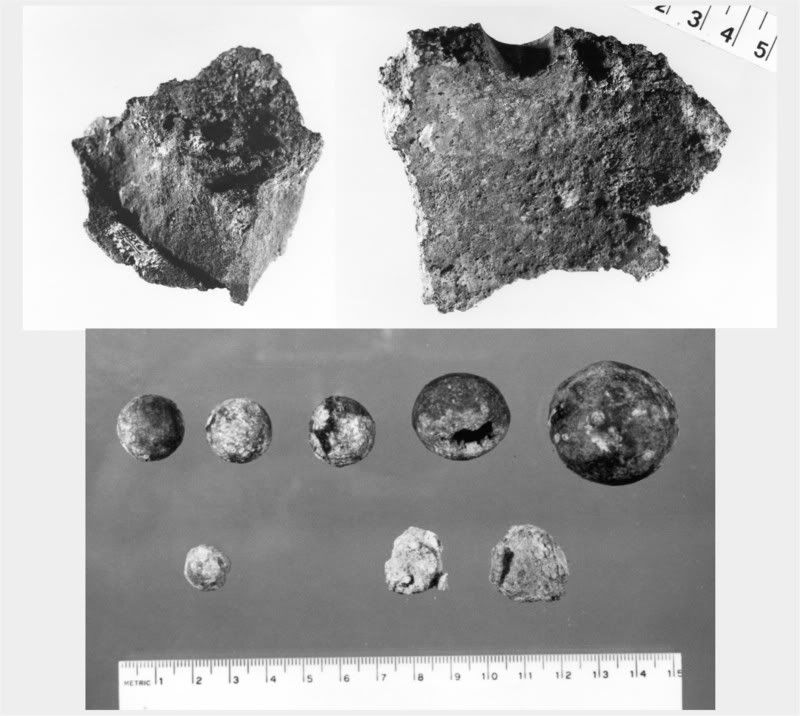

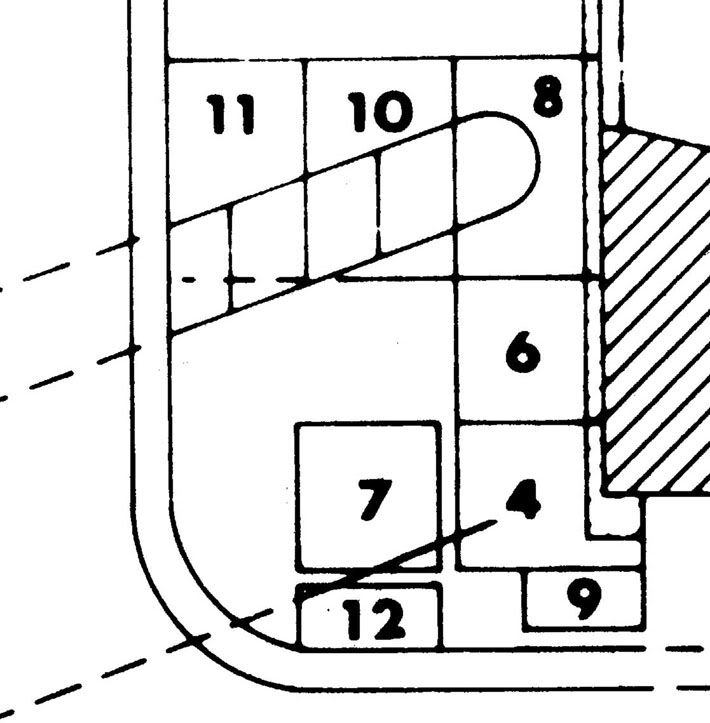

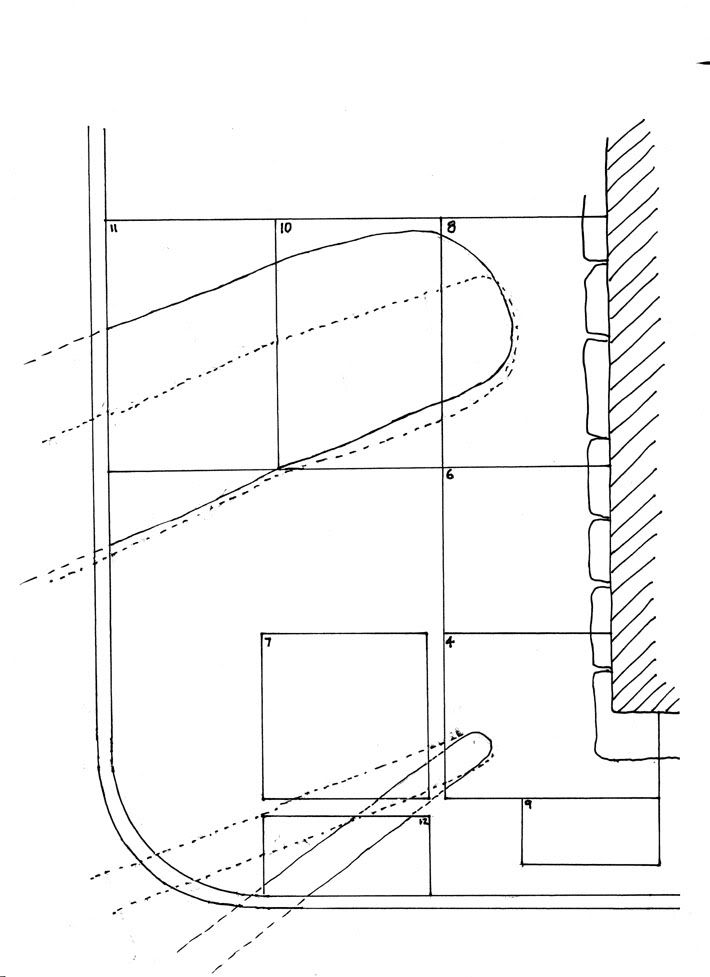

In March, 1977, and with a budget totaling $483, the Center for Archaeological Research (UTSA) entered into a contract with the City of San Antonio to conduct archaeological investigations in front of the Alamo Church. Dated flagstone paving put down in 1934 was scheduled to be replaced by the City as a part of the revitalization of Alamo Plaza and this work offered archaeologists an opportunity to study the church’s foundation. The project, focused just south of the main church entrance, also allowed an investigation of a 3 meter strip in front (west) of the church. The scope of the excavations was relatively limited and only 12 units were opened. Soon after crews arrived on site, a grid was established relative to the front face of the church and 1 x 1 m2 and 1 x 1.5 m2 units were staked out. The flagstones and most of a gravel sub-base had been removed by City workers prior to the beginning of the project. Two main areas were selected for testing by the Project Investigator Dr. Thomas Hester and Field Supervisor Jack Eaton. A group of four 1 x 1s was placed around the column pedestals south of the doorway (Units 1-3, and 5), and a second group was laid out around the southwest corner of the building (Units 4 and Units 6-12). Eaton, 1980, figure 3: Plan view of excavation units and features in relationship to the church. Archaeologists began by scraping away the remaining thin layer of gravel that had served as a base material beneath the removed flagstone paving. Square nails and some 19th century artifacts were seen near the bottom of this thin layer, leaving archaeologists to speculate that they were in fact just above Republic of Texas and colonial zones. Directly below this zone and across almost all of the units were two relatively dense hard-packed caliche-gravel lenses on either side of a dark brownish gray soil. The zones of caliche represent a leveling and paving of the area in front of the church. The first caliche lens, approximately 20 cm thick, was an off-white to cream colored zone containing numerous artifacts including square nails, bottle and window glass fragments, ceramics (Spanish Colonial, Mexican, English and Native American wares), and small scattered bits of charcoal. Based on the artifact assemblage, it was surmised that this layer had probably been deposited in front of the shrine sometime between 1805 and 1810. Later period artifacts were considered intrusive and thought to have worked their way down into the zone. Two post holes were observed in Units 1 and 3, south of the southernmost column and a third was recorded in Unit 12 southwest of the corner of the structure. It was postulated that these postholes were dug through the caliche in 1849 by the U.S. Army Quartermasters Corps to support scaffolding used during the repair of the building. Below the uppermost caliche layer and also stretching across most of the excavation units was a thin (ca 4 cm) layer of brownish gray soil containing ceramic sherds of majolica, Goliad and plain wares as well as cut nails, animal bones and scattered pieces of charcoal. Numerous fist-sized chunks of limestone scattered across the area appeared to be resting on this surface. The lens was classified as dating to the Spanish colonial mission period based on the artifact assemblage and the relative position of the zone. Remnants of bottle glass and other later historic period items were considered to be intrusive to this layer. It could not be determined whether this thin lens was intentional but it is possible that it was created sometime around the collapse of the first church and prior to the beginning of the second shortly after 1757. A second caliche layer, this one beginning only 40 cm below the flagstone paving, constituted the next cultural zone in front of the church. This stratum, averaging between 10 and 15 cm in depth, included a similar array or artifacts including majolica, Goliad, and plain ware sherds, square nails, animal bones and a few bottle glass fragments. It is thought that this layer of caliche probably represents an initial “paving” episode in front of the church. A similar caliche layer dating to the mission period has also been noted by archaeologists Greer (1967) and Schuetz (1973) north of the church and convento courtyard. This zone is thought to have been laid down sometime after 1744 when the first stone church was begun. Excavations continued below the caliche-paved areas and into a relatively thick (20-35 cm) zone of very dark brown clay loam which represented the developing ground surface in this area before construction of any permanent structures. The upper few centimeters of this zone contained early Spanish colonial ceramic fragments including majolica, Tonolá, and Goliad wares. Two small triangular arrow points were recovered from this zone in Unit 8 (below the Baptristry window) and cow or bison bones as well as chipping debris were recovered from all excavation units at this depth. Artifact densities quickly tapered off and became sterile as the dark brown clay loam transitioned into a reddish brown clay loam. A thick lens of river cobbles was present near this transition zone and appears to represent a natural gravel deposit. At a depth of about 140 cm, and well below the cultural material bearing strata, a level of grayish brown granulated sterile caliche was encountered. Excavations were closed soon after this zone was reached. Excavations in front of the church. Top photo (Eaton, 1980, figure 8a) shows Project Investigator Dr. Thomas Hester standing near the corner of Unit 4 at the southwest corner of the church. (Eaton, 1980, figure 10a: View from the top of the church looking down on excavations in progress. Description of Features Palisade Trench The short segment of palisade trench recorded near the southwest corner of the church has been the topic of discussion both because of the importance of the subject matter as well as the inherent ambiguity that works its way into many archaeological subjects. This matter has been further complicated by the fact that project notes and profile drawings made at the time of the excavations can not be located within the project folder on file at CAR and it is uncertain that they ever were added to the collection. A single plan view drawing of what Eaton refers to as the palisade trench is included in the 1980 report (and below) which shows a ditch-like feature cutting diagonally across Units 8, 10, and 11. Absent in the drawing are details including post mold sizes and locations. I have only been able to find a single photograph of the feature (also shown in the report and below) and it appears that these figures are the only visual representations of this important feature uncovered during the 1977 excavation. No sketch was ever made of a supposed southern trench running across units 4, and 7 (and possibly 12?). It is clear from the photograph showing excavations beginning at the palisade trench that the possible southern trench in Units 4 and 7 had already been removed. This leaves the written account of the features from Eaton’s report and the recollection of crew member Jake Ivey to describe the archaeological remains of the defensive works. Eaton outlined the features as follows: The old backfilled trench was first noted as a slight depression and soil color change within the upper level white caliche. The trench began about 65 cm out from the building wall and extended southwest (250° magnetic) to as far as the old sidewalk curb, located three meters from the wall. The trench did not follow beyond the curb since that was the area of the old street and was very much disturbed. The trench averaged ca. 70 cm in width and ca. 45 cm in depth. The fill consisted of mixed soil types including caliche, but generally dark gray to brown in color with inclusions of artifacts and many animal bones. The artifacts included a variety of lead and bronze balls, ranging from pistol and musket balls to large canister shot. Two large fragments of 8-inch howitzer spherical shells (bronze), one exhibiting part of a fuse hole, were also found. Other artifacts include metal and bone buttons, square nails and other objects of metal, fragments of bottle and window glass, and a variety of pottery sherds.

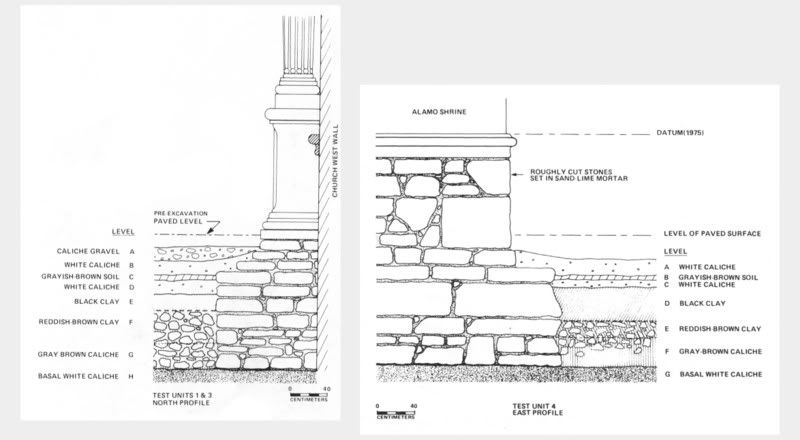

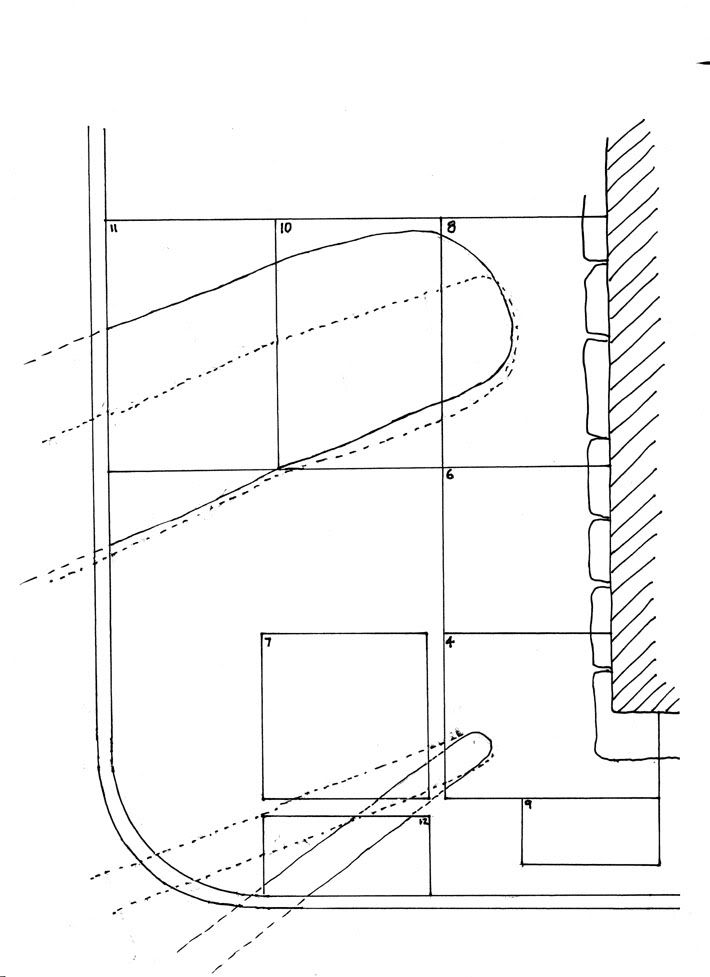

Also during excavations, traces of what appears to have been the edge of a second palisade trench were uncovered in Units 7 and 12. The remnant of this second probable trench is located 1.90 m (6 ft.) south of the first trench, extending parallel with it, and is of the same orientation.  Eaton, 1980, figure 10b: Photograph of the northern palisade trench feature. Eaton, 1980, figure 11: Plan and profile drawings of the northern palisade trench feature. (Note, the two drawings are not to the same scale; the centimeter scale at the bottom pertains to the bottom drawing.) Eaton made no mention of post molds within or immediately adjacent to either of the trench features. He also noted that the palisade trenches did not appear to abut the church wall but rather left a narrow space (ca 65 cm) by which individuals could pass. Eaton only briefly outlines his theory about the relationship of the inner (northern) and outer (southern) trench features in his 1980 report. Here, he cites Frederick C. Chabot’s 1937 description of the palisade to support his idea that the palisade consisted of two parallel rows of cedar piles filled with earth excavated from a ditch in front. Ivey’s description of the southern trench offers additional details not mentioned in Eaton’s report. He describes this southern trench as being “U-shaped…(with)…post-molds visible here and there in it -- we could see the posts were set in vertically.” He also noted that the posts “…were set so that at intervals there was a two-inch gap between these big posts.” Immediately outside (south) of the palisade trench, Jake observed additional post-molds “…of what appeared to be split posts -- that is, they were round on one side and flat on the other. They were either driven into the ground, or set into individual holes we couldn't see. They were just about against the south face of the U-shaped ditch with its line of posts. The impression we had was that the posts in the U-shaped ditch, and the split southern posts were set to cover these gaps on their south side. To summarize, Ivey suggests that rather than the two edges of a massive palisade as suggested by Eaton, it is in fact the southern “U” shaped trench and associated post molds originating near the southwest corner of the church which actually represent the remnants of the 1836 palisade. I will reiterate here that the whereabouts of any drawings or photographs of this southern feature are unknown at this time. Ivey supports his argument by noting that no post molds were ever observed or noted in the northern ditch and that the presence of quantities of battle trash within the feature suggests that it was likely open at the time of the battle. Ivey summarizes his theory as follows: Based on the maps and archaeological evidence, it appears that the narrow, southern trench was the actual palisade wall as shown on Labastida, and the northern trench was a narrow excavation probably made to supply the earth for a banquette, or firing step, against the northern face of the palisade, and to be a space where the defenders could step down to get their heads below the firing slots left in the palisade wall -- firing slots that were protected for part of their height by the posts set outside the southern trench. You protect this single wall of logs with a packed earth padding against its exterior, taken from a ditch that, if dug on the outside of the defenses, adds a further defensive ditch as well. It is worth noting here that the sheer volume of material required to fill a 6 foot wide space to a height of around 6 feet for the entire length of the palisade would be on the order of 153 cubic yards. This is a very sizable quantity and would have required a massive excavation in front (or behind) the defensive works. No such feature has yet been identified. It has also been demonstrated that extremely thick walls are actually very difficult to defend because of the difficulty of the defender to fire down over the outer edge without exposing himself to enemy fire. The Church FoundationThe principal discovery related to the exposed portions of the church footing and foundations was their massive size. The structure rests on the foundation just 24 cm below the current surface where the structure expands out to an estimated width of four feet. The foundation continues down to the caliche level some 84 centimeters below the current flagstone paving. Pieces of old flagstone observed near the juncture of the wall/foundation were thought to possibly date to the mission period. Eaton described the foundation wall and footing as follows: The foundation is constructed of large, load-bearing irregular stones and slabs which are roughly dressed on the facings and maintain fairly even coursing and alignment. These stones, which are generally around 10 to 20 cm in height and roughly 20 to 40 cm in length, are laid in rough horizontal coursing, using gray to occasionally pink sandlime mortar and many spalls to fill the larger mortar joints and to aid in setting the stones.

The footing upon which the foundation wall rests is not as carefully built, and uses rubble stones and slabs set without coursing in yellowish sandlime mortar. It appears that the footing trench had been dug through the dark brown clay to the underlying base caliche, a depth of more than a meter. Stones and mortar had been placed into the trench to provide the footing. These were not merely dumped into the trench but were carefully set to bear the load. It seems possible that the footing had been installed some years prior to the construction of the foundation and might be the footing which supported the original stone church that subsequently collapsed.

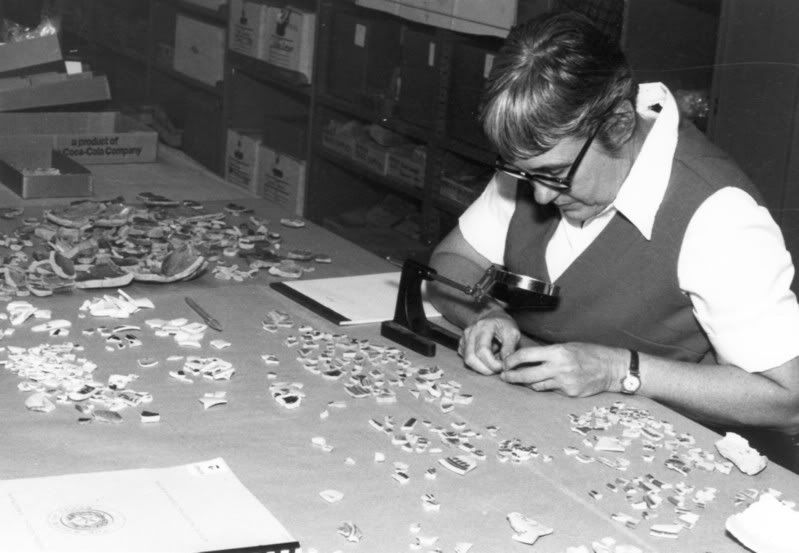

In building the church, there seem to have been three distinct construction phases (1) a foundation footing resting upon basal caliche which was placed within a footing trench; (2) a foundation wall installed upon this which rose above the old ground surface; and (3) the church walls, slightly less in thickness, which rest upon the foundation.  Photograph showing the condition of foundations in Units 4, 6, and 8. Eaton 1980, figure 9b (left) and 9a (right): Profile drawings showing foundation construction. Hearth FeatureA small shallow fireplace was noted in Unit 5 (immediately southwest of the church door) at the top of the brown clay loam surface. There were no stones associated with this feature but charcoal and ash were present across the heat-colored reddened clay surface. The feature appeared to have been bisected during the excavation of the church’s footing trench. Anne Fox works at the CAR lab classifying ceramic sherds. Military artifacts recovered during excavations include: fragments of an 8" bronze shell; .48, .69, and .70 cal. lead musket balls; and bronze cannister or grape shot. Additional Information:I will post additional information soon about artifacts recovered during this project. A copy of much of the report written by Jack Eaton is available online at the Alamo de Parras website (*Note: broken link; it's necessary to copy the complete URL and paste it into the address pane of your browser to access the following webpage): www.geocities.com/the_tarins@sbcglobal.net/adp/history/archaeology/excavations/toc.htmlJake Ivey also outlines a more complete argument against the Eaton report’s conclusions related to the palisade wall at: [ftp]http://www.tamu.edu/ccbn/dewitt/adp/central/forum/forum40.html#south_wall_3[/ftp] Finally, a discussion about other possible errors contained in the Eaton report can be found in the Alamo Studies Forum at: [ftp]http://www.alamostudies.proboards58.com/index.cgi?board=alamohistory&action=display&thread=1183563397[/ftp] |

|

|

|

Post by stuart on Dec 31, 2007 4:36:05 GMT -5

Fascinating stuff Bruce. I do appreciate this level of detail and as ever find it sad that so much of it is generally unknown or forgotten - not, I hasten to add a peculiarity of Alamo research by any means

|

|

|

|

Post by marklemon on Dec 31, 2007 8:27:58 GMT -5

Bruce,

Thanks for posting this. I thought I was pretty familiar with most of this information, but had never noticed the reference to a "shallow fireplace" in unit 5, just outside and southwest of the main entrance of the church. Is there any idea when this dates from?

Mark

|

|

|

|

Post by elcolorado on Dec 31, 2007 10:01:29 GMT -5

Bruce

My thanks for posting this most valuable and fascinating information. The pictures and the diagrams you provided have helped me to reconcile much of what I've read on our "palisade thread".

Glenn

|

|

|

|

Post by elcolorado on Dec 31, 2007 10:22:48 GMT -5

I noticed Zaboly's illustration in "Blood of Noble Men", earth is piled-up against and outside the palisade. But isn't that contrary to what we currently believe or is it possible that we should be looking at a palisade with packed earth against it's exterior?

Glenn

|

|

|

|

Post by bmoses on Dec 31, 2007 14:55:27 GMT -5

Bruce, Thanks for posting this. I thought I was pretty familiar with most of this information, but had never noticed the reference to a "shallow fireplace" in unit 5, just outside and southwest of the main entrance of the church. Is there any idea when this dates from? Mark Mark, In the report, Jack Eaton didn't speculate as to the origin of the hearth feature and evidently didn't try to C14 date it. Of course, that probably wouldn't help in this case since the potential error factor in carbon dating the charcoal would probably be quite significant. However, he did note that it was sitting on the top of the dark brown clay loam surface and he also mentioned recovering two chert arrow points from this same surface between 4 and 6 meters to the south in Unit 8. The points are "Guerrero Points" or "Mission Points" and are quite common during the mission period (occasionally even made from chipped glass). Because he also associated early colonial ceramics with the uppermost portion of this zone, I would presume the hearth was created during the original mission settlement at the site between 1724-1744. Of course it is also plausible that it could be from a pre-Spanish aboriginal campsite, but it would likely have have been used immediately before the establishment of the mission as it did rest at the top of the dark brown clay loam zone. |

|

|

|

Post by bmoses on Dec 31, 2007 19:27:45 GMT -5

I noticed Zaboly's illustration in "Blood of Noble Men", earth is piled-up against and outside the palisade. But isn't that contrary to what we currently believe or is it possible that we should be looking at a palisade with packed earth against it's exterior? Glenn Glenn, I think that raises a good question and the scenario of packed earth against the exterior of a palisade wouldn’t be out of the question with Jake Ivey’s interpretation of the archaeological remains. Because Jack Eaton, while writing his archaeological report, cited Frederick Chabot's reference to a double row of palisades with earth packed between, I wanted to find out a little more about Chabot’s description. I spoke with Tom who has a 1936 copy of Chabot's The Alamo: Mission, Fortress and Shrine. He forwarded me the following passage referring to the palisade from page 38 of his book (although Eaton cited page 24 from a 1941 edition): The entrenchment to protect the front of the chapel which faced west, and the south side of the garrison, or old monastery, consisted of a ditch and breast-works, and a cedar-post stockade. So, there is no mention of a double row of palisades in Chabot’s 1939 edition. Tom did find a reference to a double row in the book, but it is related to fortifications Cos threw up around Main Plaza in October, 1835. In the description, Chabot doesn’t cite the source but Tom discovered that it is actually from Chester Newell’s History of the Revolution in Texas [1838], page 69: The buildings were of stone, strong, and many of them fortified, especially those about the public square, where General Cos had entrenched himself with the greatest possible care, by making a strong breast-work in each opening; by cutting a fosse or trench about 8 ft. deep; by sinking two rows of piles about 6 ft. apart, filling the interstices with earth taken from the trench; and by tying the tops of the piles with rawhide ropes. Could Chabot have extrapolated this information and concluded that the palisade of the Alamo was constructed along the same lines? I would like to see a copy of the 1941 edition that Eaton cited to see exactly where the “double row of palisades” reference came from. Tom also noted that the origins of the double row of palisades theory started much earlier than Chabot: Reuben M. Potter, in his 1860 account of the battle, made no reference to a double row of palisades between the church and low barracks. By the time of his 1878 edition of "Fall of the Alamo," he had expanded the discussion of the layout of the fort to include a description of the palisade as an "intrenchment" that "consisted of a ditch and breastworks, the latter of earth packed between two rows of palisades, the outer row being higher than the earthwork." |

|

|

|

Post by marklemon on Dec 31, 2007 22:04:58 GMT -5

I noticed Zaboly's illustration in "Blood of Noble Men", earth is piled-up against and outside the palisade. But isn't that contrary to what we currently believe or is it possible that we should be looking at a palisade with packed earth against it's exterior? Glenn Glenn, While the original intent was to have a single palisade row of cedar posts, with an outer embankment of earth, the Mexicans never completed the ditch extension running from the lunette/tambour, which would have provided the earth for this outer layer. The earth excavated in the northern palisade trench was utilized to make the banquette (firing step) and was not nearly large enough to have provided enough dirt for the outer layer. Therefore, if there was an outer coating of earth on the southern face of the palisade, it is not known where it could have come from. Jake's position, and I concur with him on this, is that the palisade never had a complete outer embankment of earth, and that only about 20 feet or so of the western end of it had this coating. Mark |

|

|

|

Post by bmoses on Dec 31, 2007 23:41:44 GMT -5

While the original intent was to have a single palisade row of cedar posts, with an outer embankment of earth, the Mexicans never completed the ditch extension running from the lunette/tambour, which would have provided the earth for this outer layer . . . Jake's position, and I concur with him on this, is that the palisade never had a complete outer embankment of earth, and that only about 20 feet or so of the western end of it had this coating. Mark I would only add to Mark's comments that while this seems to be a logical conclusion based on the 1989 fieldschool where the outer trench running east from the lunette was seen to begin tapering off (as though the work crew had been suddenly recalled into the confines of the compound), there is still a rather extensive and unexplored area lying between the 1977 excavations and the 1989 field school area. Excavations over the three days in March, 1977, did not extend far enough south to sample for trenches in front of the palisade in that area. Basically, these two projects ('77 & '89) bookended the bulk of the palisade which remains as yet unexplored. Although the Plaza was extensively reworked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, I'm sure there is more than a few hidden clues yet lying beneath the surface. With plenty of archaeological work remaining to be done, the palisade area would be a great candidate for thorough and extensive excavations ; ) |

|

|

|

Post by elcolorado on Jan 1, 2008 17:08:49 GMT -5

Without question, the palisade, at the time of the battle, was a single row of posts with a firing-step. But I wonder...what would it have looked like if Cos' engineers had finished it? In my post on the "Alamo as a Refuge" thread, I theorized that Cos utilized the Alamo as a supply depot and infantry barracks. But I think the primary purpose for the Alamo, as Cos viewed it, was to provide battery support for military operations conducted outside the fort. In short, Cos fortified the Alamo for battery use and not infantry use. Hence, the insufficient number of firing-steps or banquettes along some of the Alamo's walls. This brings me back to the palisade. As Bruce pointed out, in the battle for Bexar, Cos' engineers had constructed a fortification or breastwork of double posts. There was a six foot space between the two rows that was filled with earth. The purpose of this fortification was to absorb artillery rounds - counter battery fire. It's width made it impractical for infantry usage. So, I was thinking, is it possible the palisade was intended to be a double row of posts? There are some indications. Some post holes discovered six feet from the completed single row and a little bit of earth thrown up against the exterior of the palisade. It could be that Cos' engineers planned on constructing a double post fortification but because of the Texans' attack were only able to finish a single row. I realize this theory may be a bit of a stretch. Just thinking.  |

|

|

|

Post by bmoses on Jan 2, 2008 13:12:02 GMT -5

Do any of you know of any other descriptions (aside from Chabot's) of the palisade being six feet wide and filled with earth? It would be nice to review the early literature on the construction of the palisade wall (first description, etc.).

|

|

|

|

Post by TRK on Jan 2, 2008 15:52:36 GMT -5

This may be the genesis of the claims that the palisade was a parallel row of pickets: Hansen, The Alamo Reader, p. 165 ff., reprints a manuscript by John Sutherland that included a critique of Reuben M. Potter's 1860 version of "Fall of the Alamo." In commenting on Potter's plan of the Alamo, Sutherland wrote (p. , "The Diagram is correct but the writer is not well informed as to details. R represents an entrenchment running from the South west angle of the chappell to the gate. 'This work was not manned against the assault.' Now this work or space was stopped by a double row of Picket, with a pitt its whole length eight feet wide & eight feet deep ever kept full of water from the ditch, running by the chappell--the ditch was made by the Mexicans during the seige, when Coss surrendered." So, Sutherland, who claims to have had some familiarity with the Alamo in 1836, was adamant some 24 years later that the palisade comprised two rows of pickets, and had a moat in front--hang the archaeological evidence  If Sutherland shared his critique with Potter, that may explain why Potter's 1878 version of his article had what the 1860 edition lacked: a description of the palisade. |

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Jan 4, 2008 14:07:17 GMT -5

We found a hearth feature, probably the one discussed by Bruce, right up against the foundation of the church just a bit south of the main door -- in fact, the hearth had been cut in half by the foundation trench itself. In this area there was an air gap in the trench between the wall footing and the side of the foundation trench that had somehow survived unfilled all that time, so we were looking down into the footing trench at the face of the foundation, and you could reach down into it and feel of the face of the trench, and the scallops left by the shovels of the excavators. Talk about getting in touch with the past.

[Note added 12/27/2011: The hearth feature I described here must have been in unit 1, against the wall just south of the second pilaster, while the one Bruce mentioned was in unit 5, a meter from the wall.]

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Jan 4, 2008 14:34:21 GMT -5

Here's a section I pulled out of the "Archaeological Evidence for the Defenses of the Alamo" article, which has some details about this sort of defensive work elsewhere in San Antonio during the 1835 fight.

In San Antonio, Cos built parapets like the one being described here [in Eaton's report] across the entrance of each street into the main plazas of the town. J. E. Field, who helped take them, described these parapets in 1836: “a ditch was dug ten feet wide, five feet deep, raised on the inner side [to form a parapet], so as to make an elevation of ten feet. Over this was erected a breast-work of perpendicular posts, with portholes for muskets, and one in the center for cannon.” [J. E. Field, _Three Years in Texas_ (Greenfield, Massachusetts: Justin Jones, 1836), p. 17.] Such a stockade was generally used to protect the defenders against small-arms fire; it was not intended to offer much resistance to artillery. [J. B. Wheeler, _The Elements of Fortification for the Use of the Cadets of the United States Military Academy at West Point, N. Y._ (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1882), p. 161.] However, if the exterior earth parapet was made thick enough, 8 or 9 feet, then the stockade wall becomes a timber revetment for a parapet, and could resist artillery like any other earthen parapet. The difference between the two depends on the size of the ditch excavated in front to supply the earthen protective blanket, as discussed in the previous section. Because this ditch was apparently never completed, the stockade remained just than, probably without any exterior earth blanket at all for most of its length, making it vulnerable to cannon fire.

...

During the siege of Bexar, Cos had made the church of Nuestra Señora de Candelaria, on Town Plaza, into his magazine and powder house. On October 22, James Bowie and J. W. Fannin reported to General Austin that behind the stockade parapets at the mouths of the streets into the main plazas, described by J. E. Field, above, the Mexican army had “8 pieces (4 lb) mounted – and one of larger size preparing for us. They have none on the Church – but have removed all their ammunition to it, and enclosed it by a wall, made of wood, six feet apart and six feet high, filled in with dirt, extending from the corners to the ditch, say sixty yards in length . . .” [James Bowie and J. W. Fannin to General S. F. Austin, Mission Espada, October 22, 1835, in John H. Jenkins, ed. _The Papers of the Texas Revolution 1835-1836_, volumes 2 and 3 (Austin: Jay A. Matthews, 1973), p. 190-91; compare with Frederick C. Chabot, _The Alamo: Mission, Fortress and Shrine_ (San Antonio: Frederick C. Chabot, 1941), p. 26. (This is the same description as presented by Chabot in earlier versions of this booklet, in 1936, 1935, and 1931)] This structure, however, was not a defensive position, but rather a “bomb-proof” or “splinter-proof” protective wall, designed to shelter explosives from being impacted by incoming shells, ball, or shrapnel. [D. H. Mahan, _A Complete Treatise on Field Fortification_ (New York: Wiley and Long, 1836), pp. 189-91; Wheeler, _Elements_, pp. 135-143.]

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Jan 30, 2012 17:12:23 GMT -5

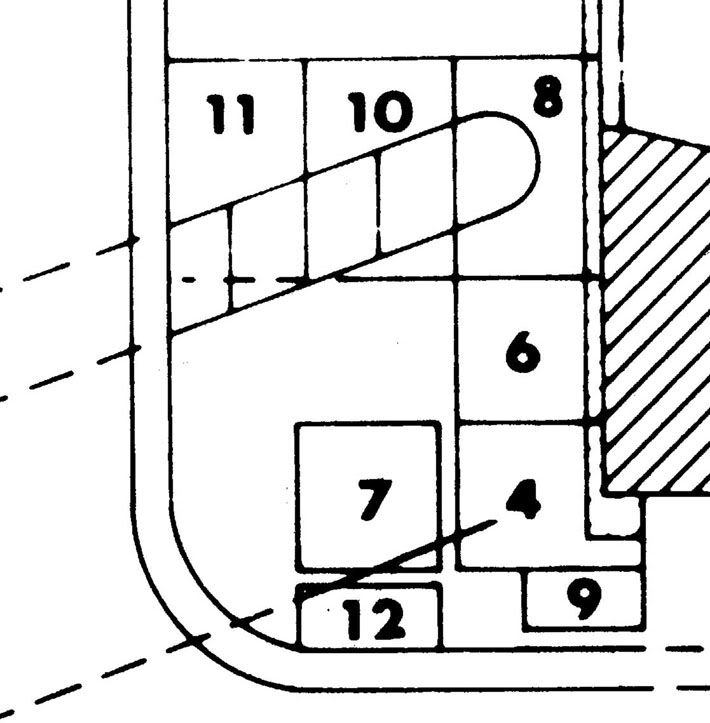

In the process of thinking about the question of ground level at the front of the church as raised by Zaboly in Altars For Their Sons, I realized that the photographs and drawings take us back only to about 1848, and that the archaeological evidence for the ground level might allow information about ground level in 1836. I looked again at Eaton’s report, Excavations at the Alamo Shrine, and his record of the excavation of the palisade trench at the southwest corner of the church. This does give us some information about ground level, although it does not allow us a simple and direct statement of what that was. In the process, I find I have raised more questions than I have answered – and I think the members of the Forum will enjoy getting involved in this. Based on Eaton’s report, the published information about the Palisade Trench has it as fairly simple. “The trench began about 65 cm out from the building wall [of the Alamo Church] and extended southwest (250° magnetic) ... three meters from the wall.... The trench averaged ca. 70 cm in width and ca. 45 cm in depth.... Also during excavation, traces of what appears to have been the edge of a second palisade trench were uncovered in Units 7 and 12. The remnants of this second probable trench is located 1.90 m (6 ft.) south of the first trench, extending parallel with it, and is of the same orientation.” (pp. 24-25) The thing is, this information is apparently wrong in a number of ways. First, Jack all but ignored the southern trench line, and focused his attention on the north trench, full of bullets, shell fragments, and other material from the battle itself. From the description quoted above, it is clear he considered what we found to have been the northern edge of a second trench of the same general size as the first one to the north, rather than the narrow ditch that I describe. He did not include any plan of this trench other than a single line showing its location (probably intended to indicate its northern edge), on his figure 3, although its existence is part of the evidence to support his interpretation of the palisade as “consisting of two rows of cedar piles six feet apart, with the space between filled with earth from a ditch dug in front” (Eaton, 1980, p. 25 – see also his discussions on pp. 8 and 47).  Second, Jack gave the angle of the trench as 110° west of magnetic north, which at the time of the excavation was 9½° west of true north. This happens to be the same bearing as the front of the church, so the angle between the front of the church and the ditch is also 110 degrees. (On p. 24 Jack says the angle was 250°, but this is the same direction measured the other way around.) Jack says on p. 8 that the palisade ran “between the southwest corner of the old church and the southeast corner of the quadrangle,” that is, the southeast corner of the Low Barracks – but as Rich Curilla and Tom Kailbourn pointed out in their discussion of this in 2007on the Forum in “Alamo History:: Paging Mark Lemon: palisade question,” located at: alamostudies.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=alamohistory&action=display&thread=44&page=2this angle would take the ditch and the trench to its south to a point on the low wall running north from the Low Barracks, about 36.6 feet north of the corner that virtually every map indicates it went to. Third, there are discrepancies between what Jack shows in his diagrams and what is visible in the photographs, in the size and angle of both trenches as shown by the (very sparse) available information. How do we reconcile the difference between the results of Eaton’s excavation and interpretation with what apparently was the actual plan here on the southeast front of the Alamo? I came up with a supposition that Jack made an erroneous calculation of the actual direction that the ditch should run in that would have been fairly close to his 110° angle, implying that he did not realize there was a problem with the angle. That may well have happened, but when you examine the photograph of the excavation looking straight down from the roof of the Alamo (figure 10a), however, you can see that its angle appears to be about the same as Jack’s plotted angle on the plans shown in figures 3 and 11. In other words, the northern trench doesn’t appear to run towards the corner of the Low Barracks. How could this be? Furthermore, the southern, narrow trench does not seem to be visible in the photograph in figure 10b, even though Jack’s diagram shows that it should show up in the south face of unit 7 at the top of the picture. But there is a strange dark blotch on this south face, in the southeast corner of the unit. Since we don’t have the field notes and unit plans and sections, nor any of the photographs other than the ones Jack included in the report and the three others (personal ones, I think, possibly by Anne Fox) that Bruce was able to find and include in his summary of this excavation, this is all we have to go on as actual evidence, other than my memory of what we saw. It is interesting to note that if the south palisade trench ran directly towards the southeast corner of the Low Barracks (and this is the way I remember its orientation running), as the maps show it, then it would have to have run across unit 7 at its southeast corner, as shown below in the plan, and the dark blotch visible in the photograph would be our only available view of a cross-section of this trench. But this raises the question: in figure 3, did Jack draw the line of the southern trench intentionally to parallel the northern one, as he described it doing, even though it didn’t, but ran about 17° more southerly? If we assume that Jack changed the angle, then the southern trench (which apparently contained the palisade wall itself) ran as the historical maps showed it doing, and the northern trench may have curved somewhat and acquired the same angle farther to the west than we were able to follow it. If Jack made this change, presumably it was because he was sure the angle shown on the field drawings of the units was wrong (essentially what I’m saying here is that he thought I had drawn it wrong, since as far as I recall I did all the recording on the trench itself) and that the southern trench actually did parallel the northern trench. Looking at that photograph in figure 10a produces some other problems as well. For one thing, the trench as shown in the picture seems far wider than the trench as shown in the diagrams in figures 3 and 11. In fact, using the sizes of the visible units, I estimate that rather than the 70 cm wide that Jack says it was, it was actually more like 110 cm. Rather than 2.3 feet wide, the trench appears to be something like 3.6 feet wide. TRK, you have some expertise in photo interpretation – what would be your judgement on this? Any of the rest of you who have abilities in this area, give it a look as well. These considerations give us the following rough diagram, showing what I believe the evidence suggests. In this plan, the southwest corner of the church is visible on the right, and Jack’s sketch of the northern trench is shown as a dotted outline. I have shown the southern trench in its approximate true size in dotted outline where Jack’s diagram has it. In solid line I have shown the apparent true angle of the southern trench, and the apparent true size of the northern trench. The double line on the left that curves at the lower left corner was a curbing that marked the edge of the “street,” and our excavations stopped there. Whether traces of the trenches might be found farther to the west is unknown.  |

|