|

|

Post by TRK on Jan 31, 2012 14:23:13 GMT -5

Jake, I enjoyed reading your thoughts on revisiting Eaton's 1980 report. First, to make it easier for readers to follow your references to the figure numbers in Eaton's report, I went into Bruce Moses's initial post above and revised his captions to identify by figure number his illustrations that were taken from Eaton's report.

On reading your most recent arguments, it struck me that perhaps we are putting too much emphasis on the compass bearings of the northernmost trench and its failure, if projected all the way to the low barrack area, to come anywhere near the southeast corner of the low barrack. Afterall, if I'm reading the diagrams and their scales correctly, only about eight feet of the northern ditch were discovered and mapped, in units 8, 10, and 11. Considering the entire ditch was probably around 100 to 115 feet long, eight feet is a pretty small proportion of the entire ditch. Would the military engineers who laid out the ditch and the grunts who dug the ditch have completed all ~115 feet in a perfectly straight line, or should we be allowing for a less than perfect entrenchment, with parts of the ditch deviating from a straight line for whatever reason?

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Jan 31, 2012 15:48:34 GMT -5

Yes, I suggested that in the fourth paragraph from the bottom in my big post above: maybe "the southern trench (which apparently contained the palisade wall itself) ran as the historical maps showed it doing, and the northern trench may have curved somewhat and acquired the same angle farther to the west than we were able to follow it." I'm imagining a very shallow crescent-shape to the wider ditch, with symmetrical slight curves towards the stockade wall itself at either end (and we've only seen the angled part of the northeast end), and the rest of it running pretty much parallel with the stockade wall.

|

|

|

|

Post by TRK on Jan 31, 2012 16:21:58 GMT -5

Ah, I must've blinked when I was reading that paragraph  |

|

|

|

Post by Rich Curilla on Feb 1, 2012 3:12:56 GMT -5

In an off-beat self-response to my own observation about the angle deviation of the palisade in the archeological diagram, I started thinking about the issue again some months ago and came up with this.......

Speculating and ignoring for a moment the primary evidence (Labastida, Sanchez-Navarro, "Jameson"...), would it not make more sense militarily to take advantage of the eastern end of the low barrack to provide enfilade fire across the front of the palisade by joining the palisade to the N.E. corner of the low barrack rather than to the S.E. corner? It seems a waste of that 15+ foot high building to have it sitting *behind* the palisade.

There is even one primary source that might support this theory. Sutherland's (possibly Sutherland's) hand-drawn plat in John S. Ford's memoirs [Hansen, p. 160] shows the palisade connecting with the south end of the "low wall" which is even with but not connected to the N.E. corner of the low barrack. If this were for some reason true, then it would be a lot closer to a target for Jack Eaton's trench as drawn.

Needless to say, Sutherland's plat defies Alamo logic as much as any others, but he does show an entrance gate between the east end of the low barrack and the low wall/palisade junction. This is perhaps the source for Potter's gate. Here we have another mystery, because the first drawings of the low barrack from the south show the building falling short of it's believed eastern end, thus prompting the theory that this portion and the kitchen were jacal or adobe structures that were destroyed by Andrade.

What if it were indeed a gate? This would explain how vehicles were able to enter the Alamo. With the supposed main gate behind the tambour being partially blocked shut by a wall or some other hard-to-remove barricade (as per Labastida) and the only other gates being a postern, a two foot wide passageway at the church end of the palisade, and a too-narrow space at the north end of the long barrack, there had to be SOME way for a wagon to get into the fort.

I realize this is far-fetched -- that there are many facts that defy it, particularly the supposed existance of the kitchen -- but placing a gate there and a shorter low wall meeting the palisade as drawn by Sutherland does match the evidence in the ground, if Eaton didn't make a mistake.

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Feb 1, 2012 20:04:17 GMT -5

Oh, man, I hate it when the voice of reason wanders into the party.

The angle Jack found for the big north ditch carries it to a point 36.6 feet north of the southeast corner of the low barracks. That's as good a distance as any for the north end of the structures that Labastida shows on his plan of the Alamo. So from the viewpoint of having a place to go, that's a pretty good one.

And the point about using the low barracks for flanking fire along the stockade (I've started calling it that because Wheeler, 1882, is quite specific about what you call which -- but the force of tradition is against me on that, so take it as an idiosyncracy) is a good one. But ...

OK, take the discussion about having to trust primary documents as givens until you have reason to doubt one or another part of it, and then start being careful with it, as already said. We can treat this as a theoretical discussion, to see if we develop doubts about all the maps we've trusted to one extent or another so far.

So: But ... if you were building those defenses, and you wanted to take advantage of flanking fire down the face of the stockade, then a gun position on the roof of the low barracks would be a great place, supported by rifle/musket fire. But it was something like 15 feet or more, probably closer to 20 feet, high, and the stockade was at most about eight feet high, so would you need to offset the west end of the stockade? Well, maybe so, because otherwise firing a cannon down the face of the stockade from the roof of the low barracks would pretty much take out all the defenders along the stockade wall. In fact, that would seem to me to be a problem no matter how you arranged the defenses here, which may be why we don't hear of a cannon on the top of the low barracks.

|

|

|

|

Post by Rich Curilla on Feb 1, 2012 21:57:23 GMT -5

Hadn't particularly meant a cannon. I was just thinking of riflemen. With guys on the end of the low barrack and riflemen atop the SW corner of the church -- and an abatis to slow and snarl the enemy, it would have been a pretty strong position. It just surprises me that this possibility would be ignored. That said, I still go for the SE corner of the low barrack as the junction with the palisade (stockade) due to the weight of the visual evidence. By the way, Jake, what does Wheeler say the difference is? Is one a generalization and the other specific, based on materials?

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen Wiener on Feb 1, 2012 22:20:00 GMT -5

Someone refresh my memory -- where can the best quality images of the Sanchez Navarro and La Bastida drawings and plats be found? I have Nelson (2 editions), but are there better ones? Thanks.

|

|

|

|

Post by Rich Curilla on Feb 1, 2012 22:57:06 GMT -5

The best Labastida I have is actually in Time-Life's The Old West series from 1975. The Texans by David Nevin, p.p. 82-83. It trumps George's because it is the whole map, it is in color and the north wall isn't sunken into the crack between the pages. LOL. Mark Lemon gave me an even larger copy of this at The Alamo Symposium a few years ago and it hangs on my wall.

As for the Sanchez-Navarro plats, the copies in George Nelson's book are probably as good as any, but don't rely on his selective version of S-N's key on either plat.

The plat that shows Cos' right-oblique does leave off the portion of the map that shows the San Antonio River, the El Potrero (spelled right) battery and the ford and foot crossings below La Villita, but everything you would need regarding the Alamo is well displayed. Again, use Hansen's translation of the key on pages 408-409 as reference for this plat.

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen Wiener on Feb 1, 2012 23:42:20 GMT -5

Many thank, Rich; I thought I had the Time-Life volume, but cannot locate it now. I'll hunt one down on the web. Also appreciate your other notes.

|

|

|

|

Post by Tom Nuckols on Feb 2, 2012 2:08:32 GMT -5

This plats v. archaeology debate is like the parable of the blind men and the elephant. S-N, La Bastida, GBJ, Gentilz, etc. are the blind men and the Alamo is the elephant. Each man recorded what he perceived of the elephant at each man's unique position in time and history. Each man's recordations were flavored by his own subjective memory (or lack thereof), drafting ability (or lack thereof), value for factual accuracy (or lack thereof), value for expedience or aesthetics, prejudices, agendas, aspirations, etc. If the fossil of the elephant is unearthed today, we can assess it objectively, free of the past subjective records of the various blind men. If the two conflict, the former should control.

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen Wiener on Feb 2, 2012 13:30:46 GMT -5

Apt analogy, Tom. I'd like to see more of this particular elephant, but who knows if we'll get that chance?

Rich - thanks; I'm going to find a copy of that book, but meanwhile there is a color reproduction of Labastida in Frank Thompson's large overview book "The Alamo." Sounds like the one in the Time-Life volume is much larger.

|

|

|

|

Post by Rich Curilla on Feb 2, 2012 20:51:14 GMT -5

Ahhh yes. I had forgotten about that one. Frank to the rescue. It is smaller than in the Time-Life book (by about half) but quite clear. I'd say that you can draw conclusions from the larger one that you might overlook on the smaller one though. But it is the same photo of the complete map in color. Interestingly, the original Labastida map is about the size of a spiral college notebook (which I had with me when I saw it). This would make it about halfway in between the copy in Frank's book and the one in Time-Life.

A highlight: Michael Corenblith was a bit shocked to find out it's true size after he created one that covered most of the table for the scene in the movie. He finally laughed it off saying "If Gary Zaboly can do it, so can I." LOL. (He had bought three copies of Blood of Nobel Men for their art department.)

|

|

|

|

Post by Allen Wiener on Feb 2, 2012 20:59:12 GMT -5

Found a NEW copy on eBay for under $10 & grabbed it. Thanks for the tip, Rich!

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Feb 2, 2012 22:10:36 GMT -5

Sorry, Rich, I just got carried away with thinking about a cannon up there. But pursuing your thinking about defensive capability in this area, look what we do have, assuming that the stockade ran the way the maps show. We have the single cannon and however many musket guys you can afford to place along the stockade wall; one of the three cannon on the church firing south, and one or both of the cannon in the lunette firing along any line from east to south, if they were in barbette, and however many men you could afford along the top of the wall of the low barracks firing south, plus a few firing east to southeast off the end of it. That's actually a strongly defended face. If you assume barbette cannon in the lunette, instead of embrasured cannon locked into two lines of fire from an embrasured tambour.

Wheeler says "A line of stout posts or trunks of trees firmly set in the ground, in contact with each other, and arranged for defence, is called a stockade. A stockade is used principally when there is plenty of timber and little or no danger of exposure to artillery fire. It is frequently used to close the gorge [the unentrenched back side] of a field work, and to guard against the work being carried by a surprise, by bodies of infantry attacking the work in rear."

The fact that this stretch of open area, which would count as a gorge, received only this defense, suggests that a) the Mexican army didn't have enough time to do more, and/or b) they thought this was enough of a defense.

|

|

|

|

Post by Jake on Feb 2, 2012 22:27:22 GMT -5

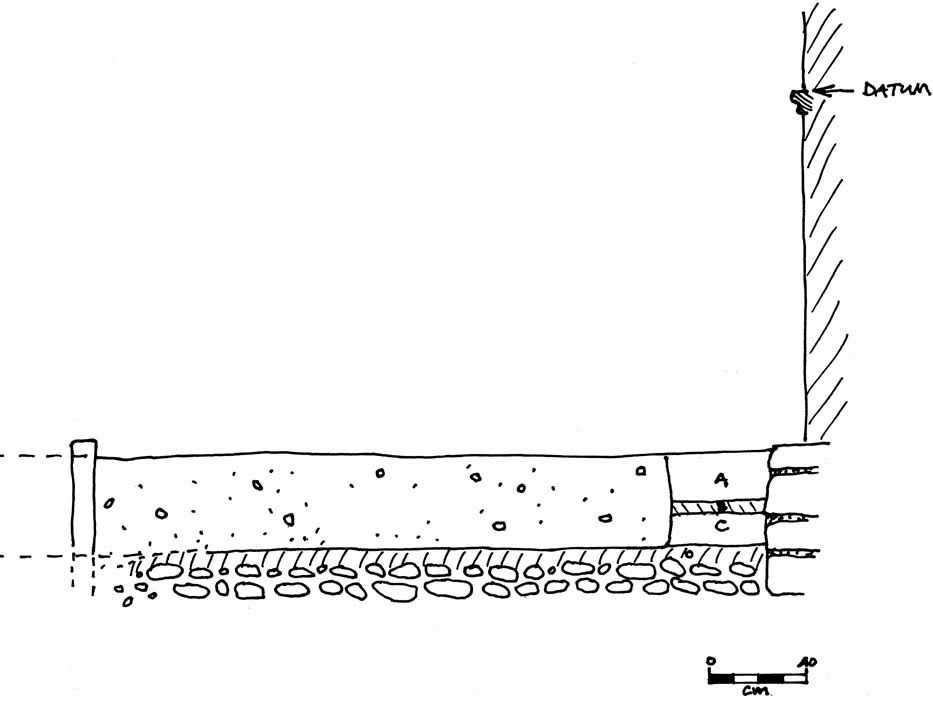

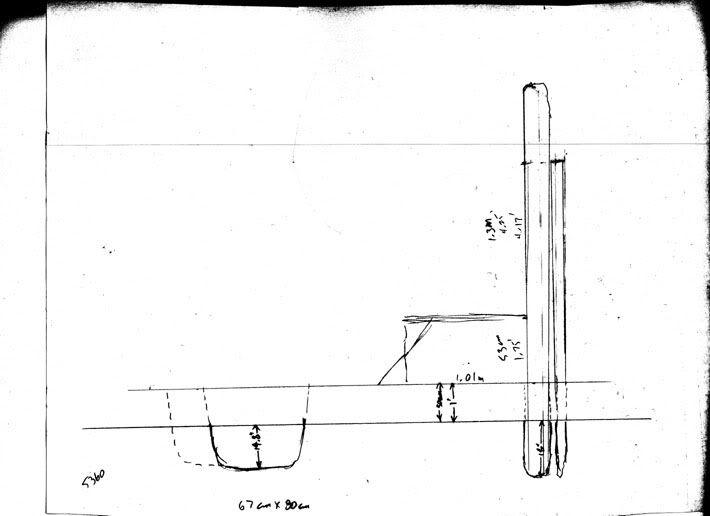

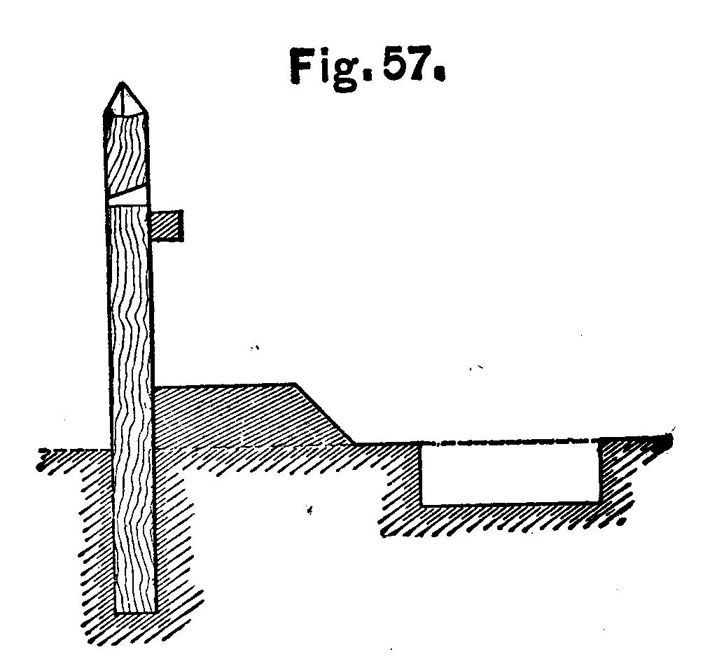

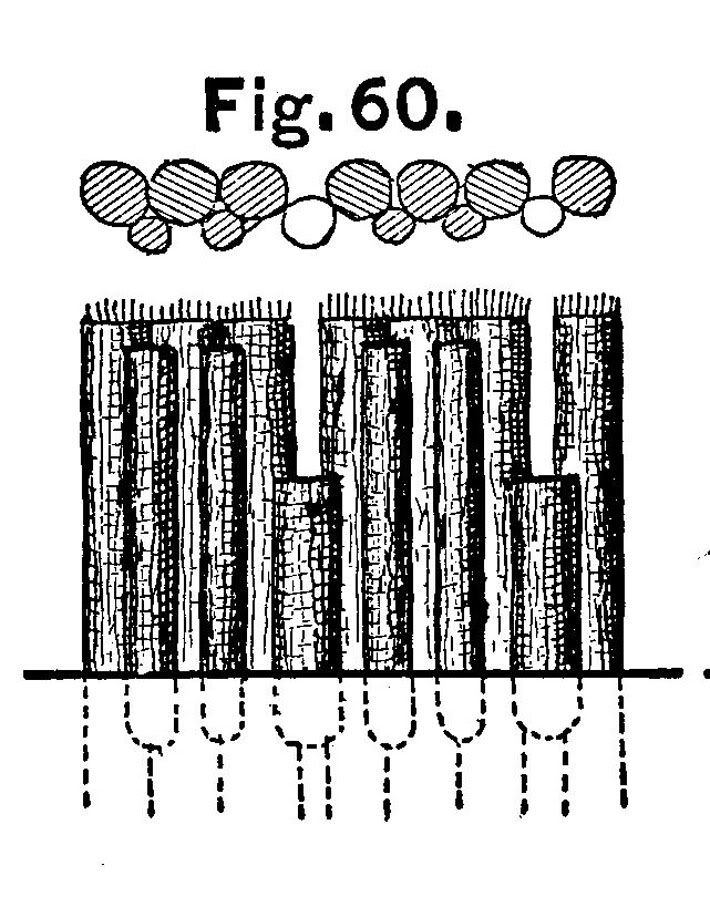

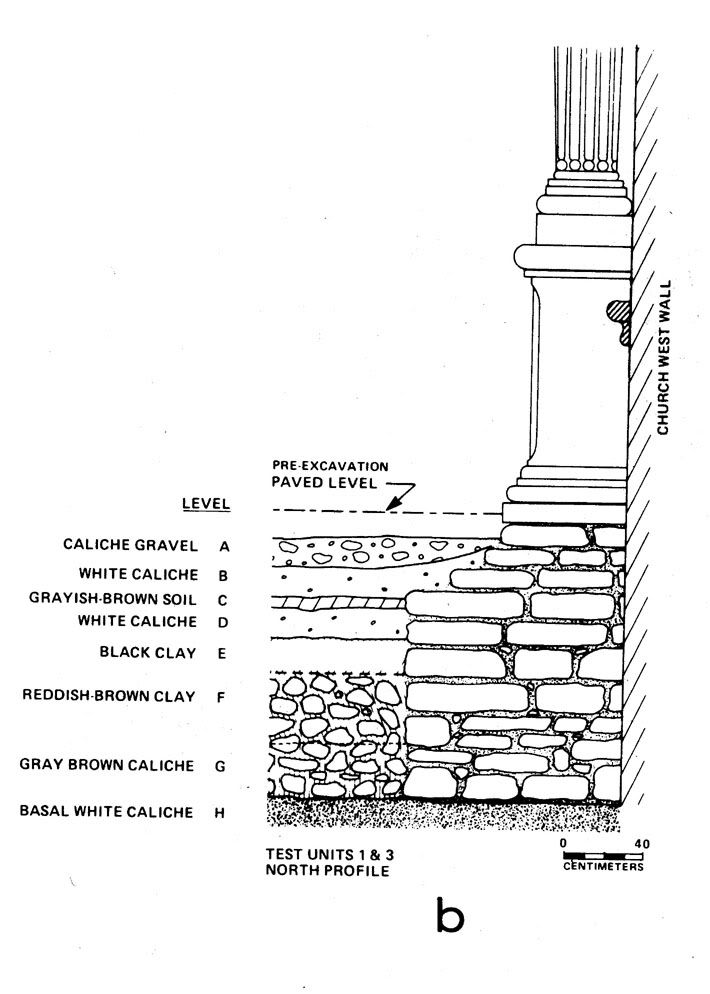

Let me put in a few diagrams here to illustrate what I think was going on along the stockade wall (call it the palisade wall if you like, we have for so long it’s probably a permanent habit). In the discussion on the palisade wall in: alamostudies.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=alamohistory&action=display&thread=44&page=2it became clear that most of the people involved did not follow the description of this defensive structure that I had put together in “Archaeological Evidence for the Defenses of the Alamo,” in The Alamo Journal 117(June, 2000):1-8. Partly this was because I left out the page reference to the cross section diagram of a palisade wall (actually, a stockade wall, according to Wheeler) in The Elements of Field Fortification by J. B. Wheeler (New York: Van Nostrand, 1882), pp. 161 and164. The book is available as a public domain online ebook at: books.google.com/ebooks/reader?id=R7VEAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&pg=GBS.PP1I included a revised sketch of Jack Eaton’s plan of the stockade wall given in an earlier post – let me add one of his cross-section drawing of the northern trench:  Given this, combined with my information about the stockade trench to the south, I came up with a sketch of the cross section of the apparent structure of the stockade, near the church.  Just a rough pencil sketch, more or less to scale, but it shows the problem here (the wider trench to the left is Jack’s northern trench, in solid, and the apparent true width of this trench in dotted). Normally, according to Wheeler, such a construction has the stockades set something like three feet into the ground, and the tops of the posts about 7 feet above ground. Wheeler shows a typical stockade looking like this:  This is his cross-section of one version of a stockade, on his page 161. This is his plan of one way of building a stockade with loopholes, on his page 164:  What we found was the bottom-most part of the ditch they were set into, and what survived was 18 inches deep. So one would expect up to 18 inches more depth – that is, the ground surface could have been up to 18 inches higher than the top surface Jack found. On this sketch, I’ve given it 1 foot, for a total depth of 2.5 feet, which would put the surface at the time of the battle 30 cm higher, or at a little above the midpoint of the square-edged base plate of the lowest-most carved pieces of the pilaster shown in Eaton’s cross-section drawing, slightly (ca. 3 cm, about an inch) higher than the surface he shows with a dotted line labeled “Pre-excavation paved level,” and that looks like the level of the surface in some of the 1840s drawings, more or less.  We know that the Army raked off a lot of fill from various places around the church and convento – the north wall excavations in the courtyard east of the long barracks (James E. Ivey and Anne A. Fox. Archaeological and Historical Investigations at the Alamo North Wall, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas. Archaeological Survey Report no. 224, Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, 1997 – you can download a copy from the CAR reports site) and Anne’s work around the tambour at the south gate found this over pretty much everywhere we’ve looked, although we don’t know how far down they took the surface in any of these areas. It appears from the photos of the front of the church in the 1860s that the tops of the foundation stones are showing all along the front, so that’s a removal of at least 45 cm, or 18 inches, in this area. So as a result of looking at Jack’s excavations, in spite of the other questions raised about them, it appears that the level of the ground at the front door of the church at the time of the battle in 1836 was at the level Jack indicated as his “Pre-excavation paved level,” which is pretty much the same level as the surface today, instead of the lower level I was willing to accept in an earlier post, based on looking at the 1860s photos. |

|